Three images here by Albert Wainwright currently on display at The Hepworth Gallery in Wakefield. Although the two below are very typical of his paintings, and very beautiful and delicate paintings in their own right, it is the one above that I think shows an artist at the height of his powers: to attempt a portrait, and we must call it that because the sitter is known (Peter Wilkinson, 1923), in which the sitter's face is mostly obscured is really the sign of a confident and assured hand, and I'd be prepared to bet money that anyone who knew Peter Wilkinson in the 1920s would have recognised him instantly from this painting without having to see his face. The paintings below are a portrait of Daniel Gill (1930) and an unidentified male nude. (c.1930)

↧

Albert Wainwright: Three Portraits

↧

Shop Window Displays of the 1970s

James Barry Wood's book, Show Windows. 75 Years of the Art of Display yielded a blog post last week on the shop windows of the 1950s that proved very popular so for this second and final post of images from the book I thought we would move to the 1970s. The dashing chaps above are from Barney's in New York, a window designed by Guy Scarangello in the late 70s. Below from top downwards we have: Frank Myers designing a window displaying bow ties for Carson Pirie Scott in Chicago in 1973; the t-shirt display from the same designer in the same shop but later in the decade; the insomniac sheep counting leaping men, again by Myers for Carson Pirie Scott; perhaps my favourite though is the last photo below of white porcelain emerging from heaps for coal like buried treasure, this by Candy Pratts for Bloomingdales New York in 1978.

Wood's book is a brilliant pictorial survey and I can't recommend it enough for anyone interested in vintage style or looking for dsiplay ideas.

↧

↧

Faeries in the Dragon Book of Verse by Gillian Alington

I have always had a soft spot for faerie painting, drawing and illustration. So I was charmed today to find these (admittedly not all illustrations of the world of faerie) in an the outwardly unpromising setting of The Dragon Book of Verse published by the Oxford University Press in 1935. They are by Gillian Alington, not an illustrator I have come across before and the only book I can find credited to her is this one. Nonetheless... great fun.

↧

Rackham Illustrates Siegfried and the Twilght of the Gods

As a bookdealer it is sometimes possible to become immune to the charms of the popular. There is no doubt about the continued popularity of the big twentieth century illustrators: Rackham, Dulac, Robinson and Nielsen. In fact, sometimes the way in which buyers often ignore the lesser known illustrators can even cause a kind of inverse snobbery to build up in the bookseller's mind: a bias against the big names. I confess I see so many books illustrated by these big names that I had stopped looking at the illustrations themselves. So it was something of a surprise to find myself leafing through the first trade edition of Siegfried and The Twilight of the Gods and, as it were, 'rediscovering' some reasons for enjoying Rackham. Of course, the story helps in the first instance, the blond and beautiful Siegfried leaps off the coloured plates like a youthful Adonis. But there is clearly more. Rackham was an astonishingly accomplished watercolourist and developed a style which is recognisable at a hundred yards. I think what struck me most, however, is the reminder this book gave me of the darkness in Rackham's work. It is easy, because he is so popular still, to file his work away in the mind as light and unchallenging: in fact, much of it is far from it. Rackham's imaginative landscape is full of the dark and twisted, and creatures of mutation and shadow.

↧

Michael Ayrton Dustjackets for Peter Green

Peter Green was a Cambridge educated Classicist who wrote novels on classical subjects. These two from the 1950s have just come my way with their brilliant jacket illustrations by Michael Ayrton, better known as a painter and gallery artist Ayrton sometimes doesn't get the credit he deserves for his illustrative work. The books are, (above) the novelisation of the life of the Roman dictator Sulla, and (below) the life of the slightly mysterious Greek figure Alcibiades.

↧

↧

Gaveston on Dartmoor: A Tale of Crazywell Pool

This is Crazywell Pool on Dartmoor. It was once thought by locals to be bottomless and the story goes that the bell ropes from a local church were hauled up here and lowered into the pool and no bottom found. It was also thought to be haunted and they say that if you should look into the pool at midnight on midsummer's eve you will see there the face of the next person in the parish to die: of course, it is difficult to avoid seeing your own reflection. It is a spooky place, for sure, and there are many other tales relating to this small lake whose built up sides are almost certainly the work of tin miners rather than nature and whose bottom is never more than 15 feet below its surface. One of them involves, perhaps strangely, Piers Gaveston, lover of Edward II. Those of you who follow me on Twitter (@CallumJBooks) will know that I spent all of last week yomping around Dartmoor in the horizontal rain and under ever-darkening storm clouds and this was one of the places I made sure to visit because of the Gaveston connection.

The story is that Gaveston was hiding out on Dartmoor (he owned land near Crazywell Pool) during one of his exiles from the court. He was drawn to the pool one night by a dream and looking into it, he saw his own face and then the face of the Witch of Sheepstor. She made a reed write a prophecy on the surface of the lake which stayed just long enough to be read before returning to ripples. It was an ambiguous prophecy as all the best ones are, in which she said that Gaveston's head, now laid low, would again be raised high. Of course, Gaveston took this to mean that he will be restored to the glory of ths court; in fact it meant that his head would literally be lifted high, without his body, onto the walls of Warwick Castle.

It transpires that most authorities on Dartmoor don't believe this story has any more background to it than a poem written in 1823 that 'made up' the story, and the same authorities tell us that the story has no independent life locally. Tracking down the poem was a genuine piece of Internet detective work. Eventually it became clear that the poem was by a Rev'd John Johns but as you might imagine with only that name, a date and a search engine to go on it was tricky. I found a number of books of poetry by the said John Johns digitally reproduced online but in none of them was the poem about Gaveston. There was a website which had four stanzas from the poem but it was clearly a longer work than that. In the end it transpires that the poem was first published in a magazine, The New Monthly, under the editorship of a Mr Campbell. It is said that when he first received the poem he was so taken with it that Campbell spent a whole evening pacing back and forth quoting bits and pieces from it that took his fancy. Fortunately for us, eventually I was able to track down an online copy of a book called A West Country Garland from the end of the Nineteenth Century, in which the poem was anthologised.

The Rev'd John Johns himself was an interesting character. He was a Unitarian minister and author of a number of books of poetry. He was admired a little in his time and wrote the Gaveston poem whilst living in Crediton. Whilst the poem is very much of its time and takes a little work from a modern reader, it is also clear that there is a poetic voice of some potential within it. Sadly, any potential was cut short by an untimely death from cholera which he contracted whilst ministering to the poor in Liverpool.

The poem itself is not sympathetic towards Gaveston and this is no surprise. Ever since Marlowe wrote him into his play Edward II, Gaveston has been cast as the bad guy who ruined the realm by distracting the King into wantonness and dissipation. I'm not well versed enough in the history to know what Gaveston was really like but I know he's unlikely to have been the sole cause of a Kingdom's troubles. Historians seem agreed that the Barons hated him for his access to the King not for his sexual relationship per se... It's too easy, however, to say that their relationship wasn't an issue at all, it was certainly something which could be used as an easy target. It is interesting to me that in the John Johns poem, although not explicitly mentioned, there are a couple of points at which there is an undertone that nods towards homosexuality. There's a hint of it in the reference to Narcissus seeing his own reflection in the pool: and again as Gaveston flies back the 'boy bosom of his king' and then one has to wonder what evil deeds the last couplet have in mind as they send Gaveston to hell for no reason that is discernible in the narrative of the poem itself. I don't imagine for a second that there is any real history to this story or to the poem but I feel sorry for Gaveston. There is a redemptive thought bumping at the back of my mind that it would be fun one day to write a folk song of this story in a way which is somewhat more sympathetic to the exiled lover of a king.

Gaveston on Dartmoor by The Rev'd John Johns.

TWAS a stern scene that lay beneath

The cold grey light of autumn dawn;

Along the solitary heath

Huge ghost-like mists were drawn.

Amid that waste of loneliness

A small tarn, black as darkness, lay,

Silent and still: you there would bless

The wild coot's dabbling play.

But not a sound rose there — no breeze

Stirred the dull wave or dusky sedge;

Sharp is the eye the line that sees

'Twixt moor and water's edge.

Yet on this spot of desertness

A human shape was seen ;

It seemed to wear a peasant's dress,

But not with peasant's mien.

Now swift now slow the figure paced

The margin of the moorland lake,

Yet ever turned it to the East,

Where day began to wake.

"Where lags the witch? she willed me wait

Beside this mere at daybreak hour,

When mingling in the distance sate

The forms of cloud and tor.

"She comes not yet; 'tis a wild place —

The turf is dank, the air is cold;

Sweeter, I ween, on kingly dais,

To kiss the circling gold;

"Sweeter in courtly dance to tell

Love tales in lovely ears;

Or hear, high placed in knightly selle,

The crash of knightly spears.

"What would they say, who knew me then,

Teacher of that gay school.

To see me guest of savage men

Beside this Dartmoor pool?"

He sat him down upon a stone —

A block of granite damp and grey —

Still to the East his eye was thrown,

Now colouring with the day.

He saw the first chill dawn-light fade —

The crimson flush to orange turn —

The orange take a deeper shade,

As tints more golden burn.

He saw the clouds all seamed with light,

The hills all ridged with fire;

He saw the moor-fogs rifted bright,

As breaking to retire.

More near he saw the down-rush shake

Its silvery beard in morning's air;

And clear, though amber-tinged, the lake

Pictured its green reeds there.

He stooped him by the water's side,

And washed his feverish brow ;

Then gazed as if with childish pride

Upon his face below.

But while he looks, behold him start.

His cheek is white as death!

He cannot tear his eyes apart

From what he sees beneath.

It is the Witch of Sheepstor's face

That grows from out his own!

The eyes meet his — he knows each trace —

And yet he sits alone.

Scarce could he raise his frighted eye

To glimpse the neighbouring ground,

When round the pool — white, dense, and high —

A wreath of fog was wound.

Next o'er the wave a shiver ran

Without a breath of wind;

Then smooth it lay, though blank and wan,

Within its fleecy blind.

And o'er its face a single reed,

Without a hand to guide it, moved;

Who saw that slender rush, had need

More nerve than lance e'er proved.

Letters were formed as on it passed.

Which still the lake retained;

And when the scroll you traced at last,

The reed fell dead, the lines remained.

On them the stranger’s fixed eyes cling.

To pierce their heart of mystery:

“Fear not, thou favourite of a king,

That humbled head shall soon be high”

He scarce had read, a sudden breath

Swept o'er the pool, and rased the lines;

The fog dispersed, and bright beneath

The breezy water shakes and shines.

He looked around, but none was near —

The sunbeams slept on moss and moor;

No living sound broke on his ear -

All looked as lonely as before.

What had he given that hour to see

The meanest herdsman of the hill!

For, bright as seemed the prophecy,

A shadow dimmed his spirit still.

And well it might! the wanderer there

Had stood too near an English throne —

Had breathed too long in princely air:

He was the banished Gaveston.

Again he turned — again he flew

To the boy bosom of his king —

Trod the proud halls his vain youth knew.

Heard woman's voice and minstrel’s string.

But double was the story told

By the dark words of evil power,

And not Plantagenet could hold

The Fates back in their own dark hour.

Beside the block his thoughts recall

That scene of mountain sorcery —

Too late! for high on Warwick wall

In one brief hour his head must be

Oh, how should evil deeds end well!

Or happy fates be told from hell!

↧

Gay History: George and Edward's Photos

The History Project in Boston is devoted to documenting and preserving the history of the LGBT community of Boston and these two charmers above are an example of how fragile such a history can be. They are George Chapin Scott and Edward F. Bernier. George died in his 80s in 2005 and, whilst he was already known to The History Project and had already donated material to them, after his death his personal belongings and photographs were ejected unceremoniously from his apartment and found on the ground outside by a neighbourhood woman called Julie Katz. Julie should stand up and take a bow because she rescued all that she could carry from the pile in front of the building and gave it over to the care of The History Project.

Edward died tragically young in a road accident at the age of 31 but many of the photos show happier times among the small gay community of the area and these ones in particular certainly raise a smile depicting a band of very gay young men enjoying the beach at Provincetown, MA.

This kind of thing happens so many times. A gay man dies, without a surviving partner and without children and a landlord, or perhaps an unsympathetic family is left to deal with their belongings and a vital and fascinating glimpse of gay life and history is just thrown to the kerb. Once again, Julie Kazt, we salute you!

The archive was pointed out to me by the wonderful Boobob96, originator of many posts on this blog including a mention of his own gay history collection featuring Roger and Frank; as well as the post which has perhaps generated more traffic to this blog than any other in which he pointed us to photos from the ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archive, including a very popular photobooth kissing scene.

↧

Early 20th Century Wood Engraving

The first half of the twentieth century saw a blossoming in the art of wood engraving. Of course, there have been some stunning works done since then but changing tastes in book illustration, and in fact, in the desire for illustrations at all, have somewhat relegated the art to the realm of the private press. It was in that first half of the last century when, as well as the finely printed and massively expensive books of the Golden Cockerel Press, for example, wood engraving was being used as the illustration method of choice in all manner of mainstream books as well.

So this little exhibition catalogue was probably rather timely. The illustrations below are from the booklet. We have, from top to bottom, Eric Gill (The Aldine Bible, 1936), Blair Hughes-Stanton (Four Poems by Milton, 1933), Agnes Miller-Parker (Through the Woods, 1936), Eric Ravilious (Almanak, 1929) and Clifford Webb (And The Runner, 1937).

Obviously, there's a lot to know and a lot to love about early 20th century wood engraving but here's Callum's idiot summary: for beautiful single lines you can't beat Eric Gill; for eroticism in long slender bodies you can't beat Blair Hughes-Stanton; and for subtlety and delicacy of light and shade in the natural world it's Agnes Miller-Parker all the way. (and so many more of course...)

↧

Dugald Stewart Walker Illustrates Andersen's Fairy Tales

These are some of the illustrations for Hans Andersen's Fairy Tales by Dugald Stewart Walker. I'm sure for some of you reading this blog that must be a very familiar name but I confess, until today, I hadn't come across any of his work before: perhaps because as an American he is not so well known here in the UK. The Fairy Tales are illustrated with colour plates throughout but as usual my eye is drawn to the black and white work, of which there is a huge amount as well from full-page illustrations like these to story headers and illustrations in the text.

I may be doing the man a disservice in my selection here because they are not all like this. There are plenty that have just a single figure with huge amounts of white space, like early Heath Robinson illustrations. But these ultra detailed black and white illustrations are quite something. It's always the done thing to compare illustrators to each other and to attempt to put them in a 'tradition' and it is certainly true that there is something of Heath Robinson and something of Harry Clarke about this chap, but he really is his own man as well and quite the best 'new' discovery I've made by simply picking up a book and flicking through it for a long time.

↧

↧

A Brilliant Book!

Kudos to R today for finding this wonder and knowing that he should bring it home. Initially it looks interesting enough: a public school story in full early twentieth century chummy gear. And of course, simply from the point of view of our interest in vintage swimwear this is interesting enough. But open it up and ta dah! Book box! and who doesn't love one of those? But it gets even better as the constructor of this little gem has decorated the inside of the box with chapter headings.. all of which register pretty high on the innuendo scale... "'Arold Reveals a Secret", "A Fettered Slave", "The Cock House Rebellion", "A Midnight Disturbance". And, in wonderfully cryptic mood, the creator of this box has also clipped just one quote from the book, a piece of direct speech: "No, you chaps, men love cause their deeds are evil".

↧

1950s Mountain Panoramas

I am enjoying these 1950s postcards with panoramic aerial views of the Alps. I've always admired the skill involved in being able to draw an 'aerial' image like this without, probably, having seen it for real. Of course, by the 1950s there's every chance of flying over the mountains, or working from photographs. But there is a much longer history of aerial views that dates back centuries before the first human flew.. I am thinking of amazing views of Venice for example, and other city 'maps' done in that style. Anyway, for now, my 1950s postcards making me very happy.

↧

The Story of the Emperor and Antony

The venerable old chap on the right is Major R. Raven-Hart, an astonishing character who, after a military career which spanned two world wars and garnered him an OBE and various foreign decorations, retired to his passion which was canoeing. To say he was well-travelled would be something of an understatement. He wrote thirteen languages and spoke five. He canoed his way down nearly every major European river (Canoe Errant, 1935), down the Nile (Canoe Errant on the Nile, 1936), down the Mississippi (Canoe Errant on the Mississippi, 1938), the Irrawaddy (Canoe to Mandalay, 1939) to name just a few. The books he wrote about his adventures may not be in the best, flowing prose but they are readable and interesting and, as one bookseller put it 'you would be hard pressed to find a page on which the word boy doesn't appear'. Everywhere the Major went he found a suitable young man to accompany him. The innocence and naivete with which he talks about his companions and his complete fascination with them is utterly charming and compelling at the same time. He is so blithely unaware of what is so wonderfully obvious to any sensible reader that it gives all of his books an underlying note of humour but one which was unintended but which any reader would appreciate with affection not with mockery. There are people working on a more detailed account of his life and it is to be hoped that they may be able to shed some more light on his defiantly homo-social lifestyle but for now we must content ourselves with one of the Major's stories.

My jaw dropped as I read this. In the Canoe Errant on the Nile, as he travels, the Major attempts to wheedle local folk tales out of the boys he is travelling with and three times he interrupts the narrative of his journey with an "Interlude" to retell one of these stories. The teller of this tale was "a handsome Nubian of about seventeen" who had been taken from his village at about the age of twelve by an Englishman with whom he lived for about four years, "No, not only as his servant! We were also very good friends" The Major was clearly as much taken with the teller as the tale, "[in] the more descriptive moments, when he raised his chin, emphasising the clean lines of his almost Greek neck and jaw, and half shut his translucent black-brown eyes, and almost sang the words as if he were reading them from an invisible score". The tale itself is just wonderful and in its most anachronistic moments feels almost a little Steampunk. And the tale he told was:

THE STORY OF THE EMPEROR AND ANTONY

It is related that in those days there was an Emperor of Rome who came to Egypt for the winter. He came all the way up the Nile in his own steamer, with his own cooks and servants and slaves. Antony was one of his slaves, but the Emperor loved him very much: he was very beautiful, he had curly yellow hair like the shavings of a plane, but soft like wool, and his eyes were blue like the turquoise in my ring, and his skin was white and very smooth, like polished ivory. He had narrow ankles like a woman, so that he could wear the anklets of a dancing-girl, and his wrists were small also. But his chest was arched like the chest of a stallion, and he was strong as a young bull. Also he had a good spirit and loved the Emperor very much, and not only for the favours he had given him.

One night the Emperor heard that a fortune-teller who used the sand lived near where the ship was anchored for the night (this was a long way from here, below Asyut), and so after supper he was rowed to the shore, and went on foot, with Antony only, to find the sorcerer. He lived in a ruined temple, full of bats. When he saw the Emperor in his robes and crown he was very afraid at first, but then he drew the sand for him. And then he was more afraid still, and said: "If I had good fortune to tell you, you would have given me the gold fountain-pen with the jewelled clip that I see in your girdle; but now I have no good things to tell you, and you will have me thrown to the jackals." But the Emperor told him not to be afraid, and that he should have the gold fountain-pen anyhow, even if the fortune was not good.

So at last he said: "The sand tells me that you must lose here to the Nile something that you are most fond of, or the Nile will take your dead body before you get back to Cairo."

The Emperor was very pleased that the fortune was not as bad as he thought it was going to be, and the sorcerer the fountain-pen and a purse of gold as well, and went back with Antony to the bank where the others were waiting, and was rowed back to his streamer.

Now, on of the things that the Emperor most loved was a golden pencil, set with diamonds and pearls and rubies; and there was an emerald in it, and when he looked through this emerald he saw many small photographs of Rome - his palace, and Saint Peter's, and the Railway Station and many more. It was a wonderful emerald because these photographs were so small that you could not see them unless you looked through the emerald, but then they were quite clear and large, and reminded the Emperor of his home.

So he took it up on deck, and threw it over the railing and said: "Nile, here is a sacrifice to you of something that I most love!" And then he went down to his cabin again and went to bed.

Next morning Antony was sitting beside the Emperor and they were amusing themselves by fishing over the rail before the steamer started. They often did this, but they hardly ever caught anything. But this morning the Emperor caught a big fish, so big that he told the cook to prepare it for breakfast. The cook took it away, but he came back almost at once, very frightened, and showed the Emperor the golden pencil that he had found inside the fish. So the Emperor knew that this was not the sacrifice that the Nile wanted.

Now another thing that the Emperor loved much much, perhaps more even than the pencil, was a camera that the King of Germany had given him. It was made in Germany, and was all gold and silver, and it took very good pictures. The Emperor had used it on all this journey, on the steamer from Rome to Port Said, and then on the train to Cairo, and then on his own steamer on the Nile, and all the photographs he had taken were good ones, so that he did not like at all to throw it away. In fact, he could think of nothing he loved more than this camera, and he couldn't throw it into the water himself, he gave it to Antony to throw in, and he almost cried when he heard it splash. But Anthony reminded him when he came down to the cabin again that he could always ask the King of Germany for another one when they got back to Rome; or he could even telegraph to him and ask for another one to be sent out to Cairo, and the Emperor decided to do this, promising the King three young slave girls and a bag of gold dust and some emeralds in exchange.

This was now the next night, after the night when they had visited the sorcerer; but in the morning when they lifted the anchor the camera was hooked by its strap to the anchor chain, so the Emperor knew that this was not the sacrifice the Nile wanted, which was a pity, as the water had spoilt it anyway.

And all that day the Emperor tried to think what he had on the steamer that he loved more than the pencil or the camera, and could not think of anything: it was not his robe, because this was only a cheap one for travelling, his good one was in Rome; and it was not his crown, because he hated wearing it. And he went to bed very unhappy.

In the night Antony slid out of bed without waking the Emperor, and kissed him, and wrote a note to say that perhaps he was the sacrifice the Nile wanted, and if not it would not matter since in that case the river would not drown him. And he left the note on the blanket, just under the Emperor's chin.

Then he went up on the deck, and went right to the end of the boat where the paddle-wheel was, and out on top of this, and took off all his clothes, and stood there naked and very white in the moon against the black cliffs and the black water; and he arched himself into a bow and dived so silently into the river that no one heard the splash.

In the morning the Emperor found the letter when he woke, and they brought him the clothes from above the paddle-wheel, trembling. And he mourned for many days, and fasted, and gave money to the poor; and he built a city in honour of his dead friend, and gave it his name. Also he had the best sculptors make statues of Antony as he had been when he was alive, many of them, but none of them satisfied the Emperor because none of them were like him or beautiful enough.

He never had another friend, and his heart turned to stone. When he died when they were making him into a mummy they found his heart all hard except where "Antony" was written on it; and the Pope, who was there because it was the mummy of an Emperor that was being made, wondered very much when he saw this, and had all the story told to him. And when he heard the story, he made Antony into a Saint and built churches to him, because he had laid down his life for his friend.

↧

Esmond Hunt's Window by Frank Brangwyn in Manaton Parish Church

At the edge of Dartmoor is a small hamlet with a name that makes it sound like an angel from an obscure and apocryphal book of the Bible: Manaton. In fact it does have a rather pleasant church, most noted for it's rood screen, a delicate and extensive piece of Medieval carving and painting on which the vandals of the reformation did their work by gouging out the faces of every last saint depicted on it.

It was the rood screen, mentioned in the visitors book of the cottage I was staying in recently that first prompted my friend Mark and I to take a stroll up the hill to visit. The rood screen was certainly impressive enough but I was rather taken by a window in the Southwestern corner. It had deep, rich colours and almost pre-Raphaelite figures. It looked something special and since Mark wanted to take some photos of the rood screen and hadn't brought his camera, we resolved to return later in our week's stay. Like any good holiday cottage, the place we were staying was well stocked with local guide books and I confess a little pride to discover that my eye had been good, the window was something special: design by renowned muralist and book illustrator Frank Brangwyn.

We returned later in the week and I discovered in the gloom of the unlit church what I had missed the first time, that the window had a notice beneath it telling the visitor who had designed it. But this time I was able to take in the details of the text at the bottom of the window. It is a memorial to Esmond Moore Hunt, son of Cecil Arthur and Phyllis Clara Hunt. He died on 7th February 1927 at the age of nineteen. This, in itself seemed worth some thought: such a large and impressive window by such a well-known artist for one so young, that seemed unusual. Also, had the window been dated 1917 or 1940, it might have been easily assumed that the young man was a victim of war.

In fact, Esmond had Down Syndrome. His death was reported as by septic pneumonia at his school in Hastings. He came to be memorialised by one of the greatest muralists of the age because of his father, a lawyer turned artist and good friend of Brangwyn. It seemed sad to me that this glorious window is now more noticed for its artist and even it's crafter than it is for the young man to whom it was dedicated. There is nothing in the church, nor in any of the books about the area that mention the window which gives any more information than there is in the window itself. This includes Pevsner, who is wonderfully sniffy as always describing the choirboys in the window as "disturbing", and I suppose he had a point, but they did reflect a young man's fascination with music. It is said that the central boy is a portrait of Esmond and the cloaked figure behind is a protective St Cecilia, patron saint of music. I am delighted to say, however, that Esmond's story is now properly told as part of a catalogue raisonne of Brangwyn's stained glass on DVD by Libby Horner, and the section on this window is the one that was chosen as an online preview and is available here through Vimeo. It is well worth ten minutes of your time to remember a sweet young man who was obviously much loved.

Frank Brangwyn Stained Glass - Manaton from Libby Horner on Vimeo.

I was very grateful in my digging around on this subject for the use of Mark's photographs and for the excellent lateral thinking skill of my friend Sue.

↧

↧

Jacynth Parsons Illustrates John Masefield

Every now and again you pick up an illustrated book and see something you haven't seen before. This seems to be happening to me with increasing frequency at the moment. Today it was this little number by John Masefield, South and East, a long and suitably fanciful Arthurian poem of quests and faeries and fantasy. It is illustrated by Jacynth Parsons. Parsons was born about 1912 and this book, published in 1929. This would be remarkable enough but is made astounding by the fact that before this book, she had already illustrated published editions of W H Davies Forty Nine Poems and William Blake's Songs of Innocence. She was hailed from the age of 15 as a prodigy and a genius as it was at that time she had her first exhibition, attended and patronised by Queen Mary. There is perhaps something a little 'girlish' in these paintings... but not much! I am always astounded at the ability of both Masefield and Walter de la Mare to attract the most amazing rosta of illustrators but Ms Parsons is one I shall be looking out for from now on.

↧

Human Figure Drawing and Berenice Abbott's Photos

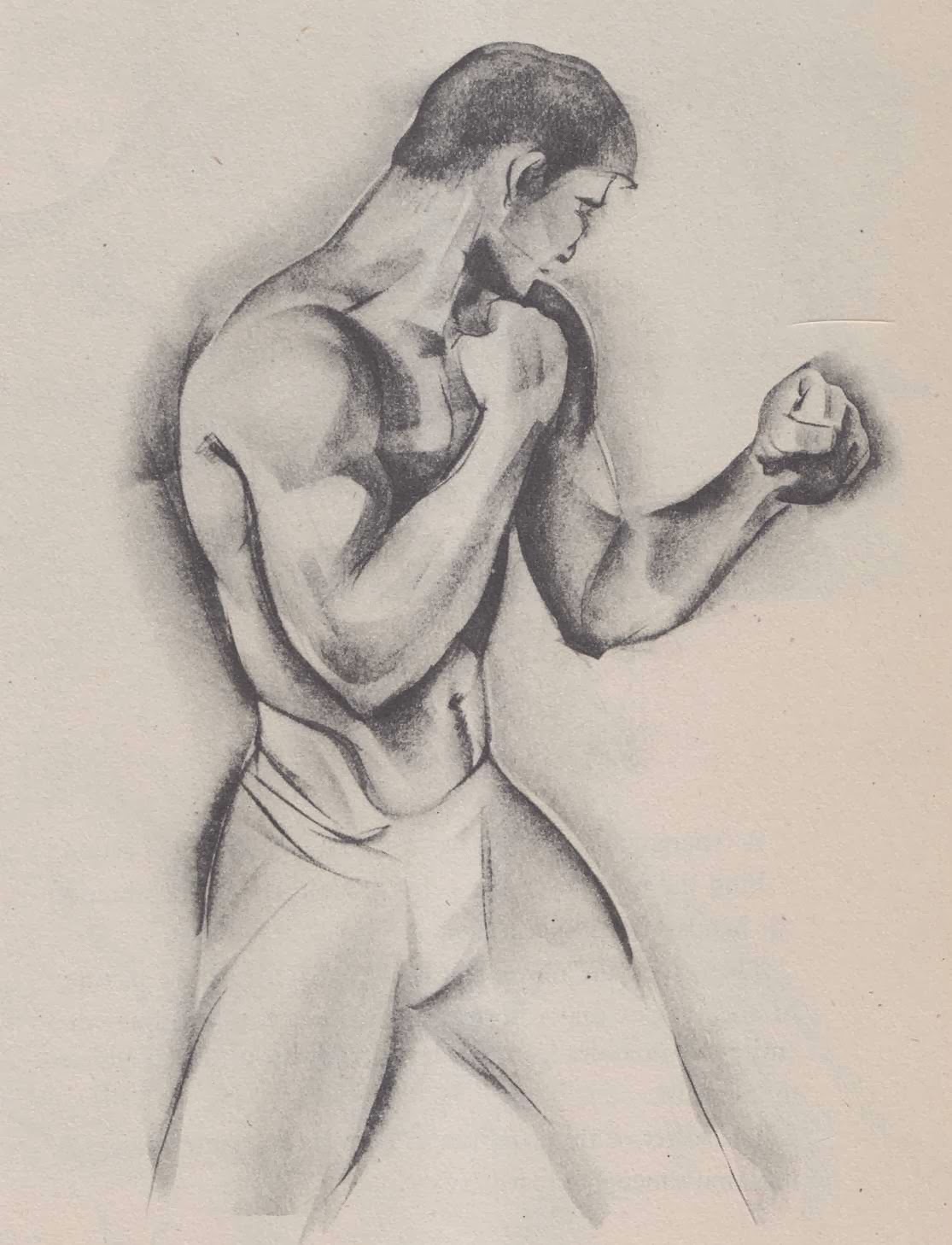

The secondhand booktrade is awash with books on 'how to draw', and in particular, 'how to draw people'. One of the things I intend to protest about should I ever reach the pearly gates along with why I never learnt to tap-dance, is why was I never any good at drawing. Books like this don't help! I assume they must be helpful to some people or they wouldn't continually be produced but I just can't see it.

This one, however, stood out. Not because it magically transformed me into da Vinci: I've not picked up a drawing pencil for years. Rather because, for once, the example drawings had some real style about them. This is Drawing the Human Figure by Arthur ZaidenBerg published in New York in 1944, which explains the somewhat Art Deco tone to the drawings. The photographs are rather accomplished too and have a separate credit on the title page to Berenice Abbott which is unsurprising given the status of this standout photographer known for her views of New York architecture and her portraits of the European literati of the 1920s

↧

Major Raven-Hart's Commemorative

↧

John Kettelwell Illustrates Aladdin

John Kettelwell is not the most well-known of illustrators but I've had this copy of The Story of Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp (Knopf, New York: 1928) for many years and have meant to share it here for almost as long. I don't really know why I haven't until now except that each time I pick the book up I become more interested in enjoying the illustrations and the story than in writing about it. Anyway, the other day I came across an illustrated copy of Stephen Leacock's Nonsense Novels and recognised the style instantly as Mr Kettelwell, so I was prompted, finally, to post some scans of this wonderful book. Too easy to say he's like Beardsley, he's no imitator, there is real imagination and style here all of his own.

↧

↧

John Gambril Nicholson. A Face Emerges

John Gambril Nicholson was a Uranian poet, a schoolmaster and a photographer. But, intriguing though his life and work is, not even his greatest fans would argue that he was a major literary figure. So when one comes across a photograph of a character like this, they can be quite scarce things. How disappointing then to see it so ravaged by time. 'Silvering' is a process that can happen to any silver-based photographic emulsion on paper over time: the silver leeches out of the emulsion and disfigures the image. So although clearly labelled and dated, the images is gone. Or is it...

The photograph below was one I have just taken of the back of the paper when it is held up to the light at an angle. It turns out that JGN, in 1894, wasn't an unhandsome twenty-eight year old!

↧

A Finger in the Fishes Mouth by Derek Jarman

2014 marks the twentieth anniversary of film-maker, diarist, activist, painter, gardener, saint and poet, Derek Jarman: one of the greatest Queer figures of the Twentieth Century. A number of events are planned but, as far as I can tell, this is the only publication to mark the anniversary.

I have said it before, and no doubt will say it again, Derek Jarman's published writings are some of my favourite books, period. For a man with such a fierce and righteous anger at the established forms of religion, the diaries are perhaps some of the most spiritual books I have ever read. Amazing then to discover that there was also a book of poetry. A Finger in the Fishes Mouth. There are poems inserted into almost all of the published diaries but, back in 1972 a small selection of his poems were put together with images from his postcard collection. That seventies edition is now almost unfindable but it is reproduced here in facsimile by the Test Centre Press who have done a great job reproducing the text and images with just enough topping and tailing in the form of both comment and information.

The poems themselves have an imagist sense of stillness at times. There is a real wit beneath many of them enough to make the reader smile and they exhibit an almost unrepeating volcabulary that rises sometimes to a near Shakespearean playfulness.

Test Centre is to be congratulated on a really important and beautiful contribution to remembering Jarman in this anniversary year.

↧

Things That Fall From Books #18: Copies of the Illustrations

The mantra of all kind of collecting is "condition, condition, condition..." Well, I've never been quite so sure and I think, actually, there are a lot of collectors out there of all kinds of things who would agree with me. I'm particularly keen on photographs and ephemera that 'show' they've had a bit of a life. These scraps of paper fell from a completely unremarkable, in fact frankly a bit crappy, copy of The Wind in the Willows. They are nothing more than someone's copies of E. H.Shepard's original illustrations for the book but they record maybe a couple of happy hours someone once spent doing something of no real consequence... the definition of ephemera!

↧